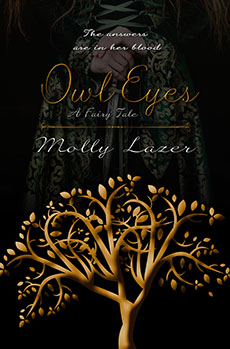

Owl Eyes

by Molly Lazer

Nora knows three things: she is a servant, her parents are dead, and she lives in the kitchen house with her adoptive family. But her world is torn apart when she discovers that her birth father has always been right there, living in the house she serves.

Nora knows three things: she is a servant, her parents are dead, and she lives in the kitchen house with her adoptive family. But her world is torn apart when she discovers that her birth father has always been right there, living in the house she serves.

This discovery leads Nora to more questions. Why was she thrown in an ash-covered room for asking about her father? Why is a silver-bladed knife the only inheritance from her birth mother? Why is magic forbidden in her household—and throughout the province of the Runes? The answers may not be the ones Nora hoped for, as they threaten a possible romance and her relationship with the adoptive family she loves.

With the announcement of a royal ball, Nora must decide what she is willing to give up in order to claim her stolen birthright, and whether this new life is worth losing her family—and herself.

BUY THE BOOK | ||

GENRE

Fairy Tale

|

EBOOKAmazon KindleSmashwords Nook Kobo |

|

| Teen | ||

Excerpt

I sat at the window with the sun on my face, slicing tomatoes I picked from the vine that climbed the back of the kitchen house. On the other side of the room, Greta hummed an old tune. The words tickled at the fringes of my memory, not quite making their way to my lips. I hadn’t heard them since she used to sing me to sleep almost seven years ago. When I was six, old enough to hold my knife, hearth-lit songs and dreams had been replaced with work.

Tomato juice sluiced across the cutting board as I bore down with my blade. The carvings that covered its handle had practically tattooed themselves on my palm. I imagined it had been the same way for my real mother—the knife had once been hers.

“Nora, Robert stopped by while you were outside,” Greta said, arm-deep in a bowl of dough. “He said there’s a new woman and her son coming sometime this week. They’re going to work here with us.”

“Why?” I said, glancing up from the mess of tomatoes on my board. The kitchen house already felt small with Greta, Peter, and me living there.

Greta shrugged. “Sir Alcander must have thought we needed the help.”

Bright pain burst through my hand. I drew a breath and looked down at where my knife had bitten into my finger.

“Are you okay?” Greta asked.

“I’m fine.” I hid my finger under the table until she turned back to her dough. I didn’t want her to take away my knife.

“Anyway, we’ll need to clear out some space in the loft.”

“Mm-hmm.” I held up my hand and stared at the red teardrop of blood glinting in the sunlight. It was beautiful, I decided. Like a jewel. I wrapped a rag around my finger before Greta could see it.

A chirrup of delight sounded outside. Siobhan and Annabelle had come out to play. Even though they rarely acknowledged me, I swore that the girls, the daughters of Sir Alcander and Lady Portia, played in view of the kitchen house just to remind me that they had the time and leisure to play when I did not.

“Greta!” Siobhan ran up to my window and leaned inside. “Do you have any chocolate?” Her voice was sweet, a voice that tried to please.

Greta knew better. “No dessert before tea.”

Siobhan’s innocent mask fell off. “I said give us some chocolate. I’ll tell mother if you don’t.”

There was a fleeting moment when I thought Greta might say no. Tell them to say please. Make them ask nicely like she would make me do if I ever talked to her like that. Instead she shook her head and went to the shelf to get the chocolate. She never would have given in to me, but my mother wasn’t the lady of the house.

“Ella-Della!” Annabelle peeked her head through the window as she reached for the chocolate.

“Not Ella-Della,” I said. “Nora.” Della was the name of the simple milkmaid in one of Annabelle’s favorite stories. Her stupidity always got her in trouble with the lord of her household. Once I had the misfortune of walking by with a bucket of water while Portia was outside, telling the story to the girls.

“Look, there goes Della now,” Portia said. At the time, I didn’t even know what the name meant, but the way she laughed let me know it wasn’t a compliment. Siobhan and Annabelle echoed her laughter and her words, and the name stuck.

“Ella-Della, we heard a secret,” Annabelle said through a mouthful of chocolate.

Siobhan shushed her. “I said I was going to tell her!”

She picked up a piece of tomato from my cutting board and threw it at my face. Warm, acidy juice trickled down my cheek. I wiped it off with my rag. Annabelle murmured in disgust at the blood that streaked the cloth.

“You’re going to want to hear it,” Siobhan said as I moved the cutting board out of her reach. “It’s about you.” She looked at Greta, who pretended not to pay attention, then back at me. “Meet us by the tree.”

“Race you!” Annabelle shouted and ran into the field. Siobhan followed. I imagined them tripping in their silk slippers and staining their dresses with dirt.

As much as I didn’t want to admit it, I was curious about what they had to say. But I also knew Greta would not let me leave until my work was done. I picked another tomato out of my basket, cut a slit into the side, and squeezed it so the slit cracked into a mouth.

“I have a secret! It’s about you, Ella-Della. Now give me chocolate!” Pulp lolled out of the tomato-mouth.

I wished Peter were here. His stories full of chivalrous heroes, brave maidens, talking animals, and the occasional fairy always made time go faster. But Peter was up on top of the main house, patching the roof again. I wished I were up there with him, outside and above everything, but Greta had insisted I stay with her.

“What if you fell off the roof?” she said as we ate breakfast.

“Then you’d heal me and make me all better,” I replied.

“Lucky.” Peter grinned as he drank the last of his tea. “She’d leave me for dead.”

“You know that’s true,” Greta said, and we all laughed. She and Peter had been married for so long that she liked to say their jokes about killing each other were sometimes serious.

I looked out the window at where Siobhan and Annabelle had settled themselves under the hazel tree in the middle of the field.

“Greta?” I said. “Can I go outside?”

Greta tsked and shook her head. “You know those girls don’t have anything worthwhile to say.”

I bit the inside of my cheek. I wanted Greta to be right, but there had been a wicked delight in Siobhan’s eyes that made me think that she really did have a secret to share. There was no way I was going to let her keep it to lord over me later.

Greta waved her hand. “Put the soup on, then go.”

I diced the rest of the tomatoes and carried the cutting board to the pot that hung over the fire in the hearth. The tomatoes went in on top of the carrots, parsnips, and rosemary that I threw in earlier that morning. I poured a pitcher of water on top of the vegetables and wiped my knife on my apron. The tomato pulp left an orange swath across the fabric.

“Now?”

Greta nodded. Her long braid fell over her shoulder as she worked. She pushed it back behind her. “Go. But you’re a glutton for punishment. And I’m not going to stop your soup from boiling over.”

I untied my apron and hung it over my chair by the window. I usually took my knife outside with me so I could use the handle to smash open the skins of the hazelnuts. Greta watched me with a raised eyebrow and the hint of a smile on her face. I left the knife behind.

I could feel Greta watching from the window as I crossed the field behind the kitchen house. Smoke meandered from the chimney, a reminder of the soup that would boil soon. The kitchen house was a squat brown-and-grey stone block compared to the massive size of the main house next to it. I could walk to the main house in minutes, but it felt like it was miles away. I’d never been inside. Greta always murmured something about my being too young when I asked if I could help bring in dinner.

Siobhan and Annabelle sat on the grass under the hazel tree. I bristled at their presence. I claimed the tree for myself long ago. It was close to the rest of the forest but set off by itself, pulsing with a secret, solitary life. I used to climb over its branches, rubbing my feet over the smooth bark and leaning my ear against the trunk to listen for a heartbeat.

It was my tree, alone and proud. I didn’t want them playing near it.

Siobhan sat with her legs tucked under her skirt, pulling up blades of grass, knotting them, and throwing them at Annabelle. She threw a clod of roots and dirt at me. It landed harmlessly an arm’s-length away. I was sure that if I hadn’t already gathered most of the hazelnuts from the ground that morning, Siobhan would be throwing them instead.

“What took you so long?”

“I had work to do.” I put my hands on my hips, trying to look imposing. Siobhan stood up and brushed off her skirt. Even though I was more than a year older, she was taller and always managed to look down on me.

“Of course,” she said, miming forgetfulness. “Ella-Della is our servant.”

“Della, Della, Ella-Della,” Annabelle sang. “Fetched some milk and met a fella.” She was ten, a year younger than Siobhan. Her face screwed up in an expression of intense concentration as she tried to remember the next part of the song.

“What is it?” I asked. “You said you had something to tell me.”

“You need to earn it, Ella-Della.” Siobhan pointed to the top of the tree where the tail end of one of Annabelle’s bird-shaped toys stuck out between the leaves.

“Why don’t you get it yourself?” I said.

Siobhan snorted. “Climbing trees is not ladylike, Ella-Della.”

Annabelle, having given up on the song, fit a chain of clovers on top of her golden curls. As she and Siobhan waited, ladylike, on the ground, I grabbed the lowest branch and swung up into the tree. There was a curved branch halfway up that I liked to sit on. I stopped there, balancing with one hand against the trunk. The toy was stuck between the branches far above my head.

“Just because it’s a bird doesn’t mean it can fly,” I called down.

Cocooned among the dark, jagged leaves, I couldn’t see Siobhan. But the leaves didn’t stop her voice from reaching me.

“Just because you look like a horse doesn’t mean you can run.”

I continued to climb. Greta was right. They didn’t have anything useful to tell me. They just wanted someone to get Annabelle’s bird.

The cloud-dappled sky came into view near the crown of the tree. The toy’s red body stood out from the green around it. I stood on my tiptoes on a thin branch and stretched to reach it. My fingers brushed against the painted wood, and it plummeted out of the tree, hitting branches and smashing to the grass below. I climbed down as slowly as I could.

Annabelle held the bird’s wooden body in one hand and the wing that had broken off in the other. Her cheeks were reddened with anger. She started to speak, but Siobhan brushed her off.

“Father will buy you a new one,” she said. “Tell him that Ella-Della broke it. He’ll take it out of her wages.”

I shuffled my feet, which smarted from landing on the ground. What did they even know about my wages? I’d never seen any of the money due to me—I always assumed Peter and Greta kept it safe for when I was older. What did I need it for, anyway? When he went to the Market, Peter used his own wages to buy me small toys or the charcoals and chalk I used whenever he or Greta had time to give me lessons. Did Sir Alcander take from my wages any time I did something he didn’t like? I’d only ever seen the man from a distance, but he seemed imposing enough that I could imagine him doing it.

“Ella-Della,” Siobhan said, “don’t you want to know the secret?”

“No.” I turned back to the kitchen house.

“I heard Mother and Father talking in the parlor. They thought I was in bed, but I was getting those black biscuits from the servants’ rooms.”

Annabelle dropped her toy back on the ground. “You said I could come with you! I wanted biscuits, too!”

“Those were for the house servants,” I said. Greta and I made the thin bilberry biscuits a week ago. It was my idea to smash up the berries to give the dough its dark color.

Siobhan went on as though she hadn’t heard me. “Mother and Father were talking and Mother said, ‘Someday she’s going to find out, and when she does, she’s going to want to know why, Alcander.’” She did a pitch-perfect impression of her mother, cocking her head just like I’d seen Lady Portia do.

Curiosity won out. “Why what?”

Siobhan opened her mouth to answer, but Annabelle got there first.

“Why you live in the kitchen house when your father is in the main house.” She gasped and clapped a hand over her mouth. Siobhan looked around. Her haughty expression was gone, replaced by guilt. She was not good at burying her thoughts. They were telling the truth.

Siobhan’s moment of humility didn’t last long. “I always thought your father lived in the oven,” she said. “That would explain why your arms are all messed up.”

I crossed my arms behind me, trying to hide the pink burns scarred onto my skin.

“You’re lying,” I said. Even if they actually heard Lady Portia say those words, what she said wasn’t possible. Greta and Peter were my parents. My real mother died in childbirth, and my father followed her to the World Apart soon afterwards. That’s what Greta and Peter always said. But the hazel tree brightened behind Siobhan’s head, and my feet felt lighter than before, like they weren’t quite touching the ground. It might have been hope.

“Am not,” Siobhan snapped. “I’m being nice. I just thought you’d want to know that your father threw you away in the kitchen house so he wouldn’t have to see your ugly face every day. See if I ever do anything for you again.”

She turned on her heels and hauled Annabelle back to the main house. I stood there for a moment, letting the colors of my small world return to normal. I couldn’t go back to the kitchen house, not yet, not if what they said was true. Why would Greta and Peter tell me that my father had passed? Was his presence the reason I wasn’t allowed in the main house? He could be there, waiting for me to come find him. Did he know who I was? Did he even want me?

“Nora!” Greta’s voice pierced through the fog of questions swirling around me. “The soup is burning!”

I ran back to the kitchen house and hefted the pot off the fire. I hadn’t put in enough water, and what I did add had boiled away. I poured in two pitchers this time and put the pot back on the hearth, hoping no one would notice the vegetables’ smoky taste. I barely heard Greta’s reprimands as I ran through the list of men who worked in the main house. There were three male servants: Matthew, Sir Alcander’s valet, was married to Sarah, the head maid. They came to work at the Runes when I was eight, so it couldn’t be Matthew. Victor, the footman, was only seventeen. The only one left was Robert, the butler. He began working at the Runes before Greta and Peter, and he was certainly old enough to have a daughter my age. He had only ever been kind to me when he came to deliver messages or get food from the kitchen house.

Someone knocked at the door. Greta opened it, and there he was. Breath caught in my throat.

“Robert.” Greta nodded, and he came inside.

“The new kitchen maid will arrive from the Vale tomorrow.”

“From the Vale?” Greta sounded surprised, but I didn’t understand why. “Is she Kindred?”

“She and Alcander are like-minded when it comes to”—he glanced over at me—“the goings-on at the Vale.”

I held Robert’s gaze for as long as I could, scrutinizing his features. He carried himself with a dignified air, stately even. He took pride in his work, which was probably why he’d been employed at the Runes longer than any of the other servants. His hair was wiry and grey. I ran a hand through the scraggily, dark red tangle on my head. I’d never met anyone else with my thick, ratty hair. Greta’s braid, while heavy, was smooth and dark. Annabelle’s and Siobhan’s curls were always brushed to perfection. Robert’s hair reminded me of trees I had seen in the woods that had been struck by lightning, an image I often associated with myself when I looked in the mirror. I could imagine his hair being the same color as mine once upon a time. His eyes were grey instead of gold like mine, but I could have gotten my eyes from my mother.

Had Robert ever been married? He wasn’t now. Maybe he had a wife who died in childbirth, and he couldn’t bear to have the child near him because she—I—reminded him too much of her. It was all very romantic. I wanted to rush over to him, but I held back. What if I were wrong? I would just embarrass myself.

Robert and Greta’s conversation ended with the determination that Peter would meet the new servants in the woods west of the Runes proper the next day. Robert brushed past me on his way out.

“Nora.” He nodded at me.

I wanted to follow him back to the main house, but as soon as the door closed behind him, I turned to Greta.

“My parents,” I said. “My real parents—do you know who they were?”

She startled at the abruptness of the question. “Why are you asking this now? Did the girls say something?”

“I just want to know.”

Greta beckoned for me to sit down with her.

“You know the answer. The couple who worked in the kitchen house before us gave you to Peter and me.”

“But those people weren’t my parents,” I said.

“They didn’t say who your parents were,” Greta continued. “Only that they’d passed, and you needed someone to take care of you. We always wanted a child, and—” She stopped talking when it became obvious I wasn’t listening. This was a story I knew by heart, but it wasn’t mine anymore.

Greta narrowed her eyes. “What did the girls say to you?”

I stood up. “Nothing.”

I went back to my seat by the window, put my apron on, and began to mash up a pile of sprigberries that Greta had put on the table while I was outside. If she and Peter knew anything about my real parents, they would have no reason to hide it from me. They gave me my mother’s knife, after all. Sir Alcander and Lady Portia obviously knew, but I couldn’t ask them. Lady Portia’s visits to the kitchen house were rare and always came with demands. Less salt in the soup or an extra dessert tart for Siobhan and Annabelle. She gusted in and out, never staying for longer than her words and never looking in my direction. Sir Alcander never even set foot near the kitchen house. The only times I’d laid eyes on him had been through a window when I brought something to Peter while he was patching the exterior of the main house. I knew Sir Alcander more by his maps. Peter had one in the kitchen house, and he used it to teach me the geography of Colandaria. Sir Alcander’s intricate compass roses were more familiar to me than his face.

No, I would not get answers from either of them. But I would go to the main house. I had to talk to Robert.

* * *

“Good morning, early riser. Any chance you made breakfast while we were sleeping?” Peter said as he climbed the ladder down from the loft and joined me in the kitchen, where I’d been trying to quiet the pounding of my heart since before sunup. He put his arm around me and kissed my forehead. The bristles of his short beard tickled my chin. All fathers should feel like this, I thought.

I had to keep myself from trailing behind him when he brought breakfast to the main house. I would have to wait until everyone was doing their work before I could go inside. I’d seen Greta and Peter go in the back door of the main house as often as I’d seen Robert, Sarah, or one of the other servants come out of it on their way across the field. The servants’ quarters were supposed to be right near the entrance. There had to be something there that would tell me about Robert.

I picked at my breakfast. The nervous flutter in my stomach made me too nauseated to eat. I’d occasionally thought about my real parents resting in the World Apart. Their ashes would have been given to the wind somewhere meaningful. Someone would have held me nearby to ensure that their spirits would watch over me. Growing up, though, I had the parents I needed. Greta and Peter gave me a fire burning in the hearth, a garden to pick food from, and stories to fill warm nights in the loft.

Now, with just a few words from Siobhan and Annabelle, I needed more.

No one would be in the main house servants’ quarters after breakfast. I waited until Peter went outside to repair the fence around the chicken coop and Greta began making her daily bread at the counter that faced away from the window.

“I’m going to see if any more tomatoes are ripe,” I said as Greta took out caraway seeds and flour and put them next to the eggs that I gathered from the coop before breakfast.

She nodded, and I headed out, glancing back to make sure that she had started on the dough. While she was busy measuring ingredients, I ran across the field to the main house and went in the back entrance. Once inside, I cracked open the first door I came to. The room I entered was about the size of the floor of the kitchen house, large enough to fit six beds. Some belongings—probably Victor’s, since Peter always complained what a mess Victor was when he came back from bringing in supper—were strewn about the floor, while others sat on shelves or against the wall. The largest bed would belong to Matthew and Sarah. That left only a few beds that could be Robert’s. A green satin vest with gold edging hung on a stand across the room. That had to be his. He would wear it to serve at Sir Alcander’s and Lady Portia’s banquets. Robert’s shelves were bare except for a few books and a tin of my bilberry biscuits.

I warmed at the thought that my father had a stash of my cooking. There was something else on the shelf, something flat enough that I couldn’t see what it was. I stood on my tiptoes and retrieved a palm-sized agate cameo. The carving was of a young woman not more than twenty years old. She was lovely, with long, wavy hair tied back with a large bow.

Was this my mother? In profile, it was difficult to make out anything specific about her features. I wished her image were in color so I could see if she had my gold eyes. I had to talk to Robert before I lost my nerve. I went back to the hallway with the cameo clutched in my fist. I didn’t know where to go, but I did know that I would be in trouble if I were caught roaming the halls. I picked a direction, glancing around each corner before proceeding as I looked for a shock of steely grey hair.

Portraits lined the hallway. All of the subjects wore the same shade of dark green that marked them as the noble family of the Runes. I stopped in front of a painting that depicted Sir Alcander and Lady Portia posing with younger versions of Siobhan and Annabelle. The artist captured the girls’ smug expressions well. The paint in Siobhan’s eyes shined with mischief. Lady Portia’s every hair was defined. The painter had arranged his light source to highlight her sharp, elegant cheekbones. Sir Alcander’s eyes were duller than those of Lady Portia or their daughters. Even Annabelle’s eyes twinkled with specks of white that were missing in her father’s.

“Nora?”

I wheeled around to face Sarah, the head maid.

“What are you doing here?”

I looked at the floor. The grey and green grain of the marble flowed like the lines on one of Sir Alcander’s maps. I ran the tip of my shoe along one of the paths.

“I’m looking for Robert,” I said. “I need to talk to him. It’s important.”

“He’s taking dictation for Sir Alcander.” Sarah looked past me down the hall. “He’ll be done soon. Come with me.”

She put a hand on my back and ushered me in the direction from which I’d come.

“You’re not supposed to be in here,” she said.

“I know.” I tucked the cameo into my pocket. “But it’s important. Don’t tell Greta, please.”

Sarah glanced behind us. The pressure of her hand on my back became more urgent.

“It’s not Greta I’m worried about.” She opened the door to the servants’ quarters and pushed me inside. “Stay here. I’ll get Robert.”

She left the door open a crack and hurried down the hall. I sat on Robert’s bed. A long piece of straw poked out of the mattress. I pulled it out from the fabric and broke a piece off the end. By the time Robert arrived, shutting the door behind him, there was a small pile of straw on my lap. I leapt off the bed, spilling it on the floor.

“Sorry.” I bent down to sweep the straw into my hand. Robert knelt to help me.

“Nora, what are you doing here? You’re not supposed to be—”

“I need to talk to you,” I said. “It’s about my—” The word stuck on my tongue. “Um, Siobhan and Annabelle said that…” I took the cameo out of my pocket. “Who is this?”

Robert snatched it out of my hand. “What are you doing with this?”

My cheeks burned. “I found it on the shelf. Is it your wife?”

The angry lines on Robert’s face softened. “No, it’s my sister. She died a long time ago. Why do you ask?”

I sat on the bed. I felt heavy enough that I might sink into the straw and never come out.

“Siobhan and Annabelle said they heard Lady Portia and Sir Alcander talking, and they said that my”—I choked out the word—“father was in the main house. I thought that you might be—”

Robert moved away, dropping the straw into a bucket next to the bed. I sank farther into the mattress. Being poked with spindles of straw was preferable to the silence in the room.

“Your father?” Robert said. “Nora, the man who was your father is long gone.”

“But you have to be,” I protested. “Your hair, it’s just like mine.”

“What, this old mess?” Robert ran a hand through his hair and sat down next to me.

My voice dropped to a whisper. “It has to be you.”

“I’m sorry, Nora. I don’t have any children. Peter’s been a good father to you, hasn’t he?”

“Yes.” I could feel each razor of straw jabbing into my skin. “I just thought—”

Wait. What did he say?

“You know who my father was!” It came out as a statement, not a question. Robert jumped up from the bed.

“No, Nora, you misunderstood. I—”

“Yes, you do!” I leapt up after him. “You said he was gone, but you know who he was. Tell me!”

Robert’s eyes darted back and forth as if he were looking for a way to escape the conversation before fixing on a point behind me. Panic tinged his voice.

“She was just bringing a message from the kitchen house.”

I turned to see Lady Portia standing on the other side of the door. I hadn’t heard it open. Waves of anger passed through her cold ocean eyes. I had only ever seen Lady Portia angry, but this was different. This was rage, and it was aimed squarely at me.

Robert put a protective arm around my shoulders.

“I’m sending her back right now.”

“Eleanor.” Lady Portia’s voice was ice cracking. “You are not permitted in here.”

“I’m sorry,” I croaked. “I’ll go back.” This was different from Sarah’s confusion at finding me in the hall or Robert’s initial anger at discovering his cameo in my hands. Different, and infinitely more dangerous.

Before I could move, Lady Portia was in the room, grabbing my arm and wrenching me from Robert’s grasp. I could feel her breath on my cheeks as she pulled me close.

“You are supposed to stay in the kitchen house,” she hissed. She jerked me out of the room and down the hall.

“Ma’am—” Robert started after us.

“Stay where you are,” Portia said without turning to look at him. “This is none of your business.”

I looked back, panicked, as I flailed in my attempt to keep up with Lady Portia’s long stride. I heard the sound of the back door being thrown open. I could only hope Robert was going to get Greta or Peter.

Lady Portia’s fingers burned on my arm as she pulled me behind her, making a series of turns through the hallways. Anytime I opened my mouth to protest, to apologize, to cry, she jerked me forwards, and my words were swallowed in a yelp of pain. She finally stopped in front of a plain, wooden door. It felt out of place next to the other doors in the hallway, which were lacquered and covered in carvings. Its austerity didn’t belong, just like I didn’t.

My wrist glowed red when Lady Portia let me go, and I rubbed my arm to quell the pain. My mouth ran ahead of me, spitting out every apology I could think of. She ignored me as she sorted through the keys on a ring she took from her dress pocket and fit a large iron key into the lock. The door creaked open. I couldn’t make out anything inside—there were no windows to let in the light. The darkness in the room felt different than when the kitchen house darkened after sunset. This darkness was hungry. I turned to run.

Portia caught my wrist and shoved me into the room. I fell on my hands and knees. Small pieces of something—dust? Ash?—rose up around me, making their way into my throat. I started to cough.

“Never ask about your father again.” She slammed the door, plunging me into the dark. The door fit so snugly in its frame that there wasn’t even a sliver of light shining at the bottom.

It was a moment before my shock allowed me to react. The room smelled scorched with death, like it hadn’t been opened in ages. I coughed again, trying to get out the pieces of the room that had infiltrated my throat, my nostrils, my eyes. I shuffled forwards until I reached the door and felt for the knob. It was cold to the touch. I pulled as hard as I could, but it would not turn.

“Robert!” I screamed. “Sarah! Peter! Greta!” I kept screaming their names until my throat was raw. The fine powder that covered the floor stuck to me wherever my body touched the damp ground. There were voices down the hall, but they were too far away for me to hear what they were saying.

“Father?” I whispered.

My arm ached where I could feel a bruise blooming around my wrist. I wanted Peter and Greta. I wanted my father and my mother, but I didn’t know their names. Only the darkness held me as I cried.